This Is Who We Are

Summer Reading Program Participants Share Their Stories

By Gaye Hill

This Is Who We Are

Summer Reading Program Participants Share Their Stories

By Gaye Hill

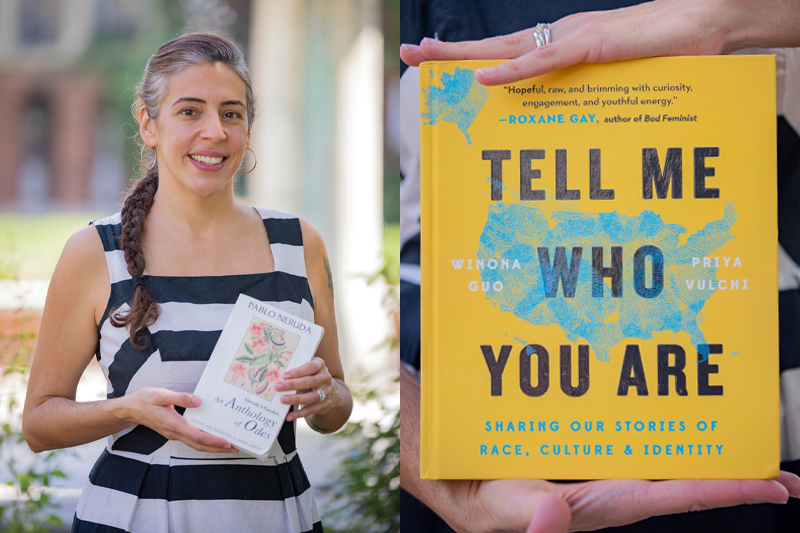

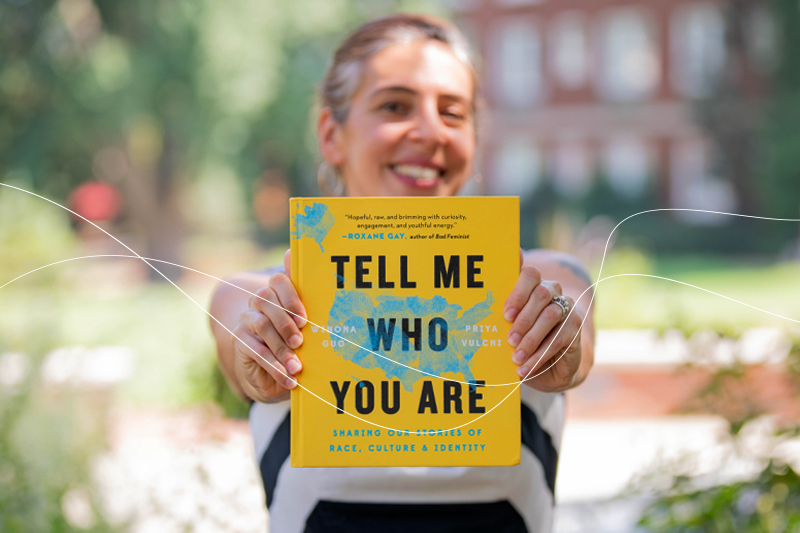

Meredith’s 2021 summer reading book, Tell Me Who You Are: Sharing Our Stories of Race, Culture & Identity, presents stories gathered by Winona Gua and Priya Vulcht, two young authors who deferred college admissions for a year to interview 150 people from diverse backgrounds across the United States. The book’s selection was guided by the College’s anti-racism initiative.

Through their book, Guo and Vulchi reveal the lines that separate us based on race or other perceived differences. They suggest that telling our stories – and listening deeply to the stories of others – are the first and most crucial steps we can take towards negating racial inequity in our culture.

The stories are accompanied by research-based, factual information about the topics raised in the interviews as well as “fun facts” that further humanize people beyond race.

The factual component of each story helps the reader to better understand the structural aspects of institutional and systemic racism. This combination of story and facts is designed to bridge the heart-mind gap identified by the authors, who explicitly move beyond an anecdotal or sentimental approach to storytelling.

Inspired by the book and guided by its framework, we invited faculty, staff, and students who plan and conduct the Summer Reading Program to share their own stories. Read on to hear what they had to say, bearing in mind that these brief glimpses by no means capture their full identities. And then, consider joining the Meredith community in reading Tell Me Who You Are and engaging in your own courageous conversations.

About Summer Reading

Meredith’s Summer Reading Program enhances the academic climate on campus by engaging incoming first-year students in a shared intellectual endeavor with the entire campus community, including students, faculty, staff, and alumnae.

Incoming first-year students are given questions to guide their reading and then engage in facilitated conversations with faculty, staff, and upper-level students during the fall semester. Students also participate in experiential learning activities related to the books. Previous summer reading selections include The Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Callings, Dimestore, and A Mighty Long Way: My Journey to Justice at Little Rock Central High School.

Dilnavaz Mirza Sharma

Summer Reading Committee Member | Bombay, India

“Most days, I would identify as a Parsee American of East Indian extraction. But on other days I might also call myself an Asian American, a woman, a North Carolinian, an American, and an NRI (Non-Resident Indian) or some combination of all of the above.

I very much think of Raleigh, North Carolina, as home, but my place of origin would be Bombay, India. I left India before Bombay became Mumbai – it is still hard for me to wrap my head around that change in nomenclature.

Before I was old enough to go to school, my maternal grandmother took care of me while my mum was at work. With her I spoke in Parsee-Gujarati. Most afternoons, she would read aloud to me in Gujarati. In the evenings, my parents spoke to us in both English and Parsee-Gujarati, moving easily from one language to another, sometimes mid-sentence.

It was in pre-school that I began to realize English would be the language that I would read, write, and speak fluently. With a new language came the realization that my cultural identity was distinct from a majority of my classmates’ and that those differences could be bridged by speaking a common language.

Generations of Parsees have largely married within their community and as a result are easily distinguishable by their appearance, language, and cultural practices. Consequently, I have always been aware of being just a little different from everyone else in the room. I have been navigating these differences for a long time, and so while impactful for sure, race, culture, and intersectionality are the very reason I am who I am. Having always lived, learned, and worked among people who are culturally and/or racially different from me has taught me that people are people and everything else is noise.”

I love biscuits! I can’t imagine not having landed in the South and never having tasted biscuits. I think my life would have been incomplete and I am only slightly exaggerating.

I took up birding during the pandemic.

I am learning to play chess. My 20-year-old son, Arya, is teaching me.

Parsees are descendants of Zoroastrians who migrated from ancient Persia (modern Iran) to India in the 7th or 8th century BC. The latest Indian census, completed in 2011, estimates that there are about 60,000 Parsees presently living in India.

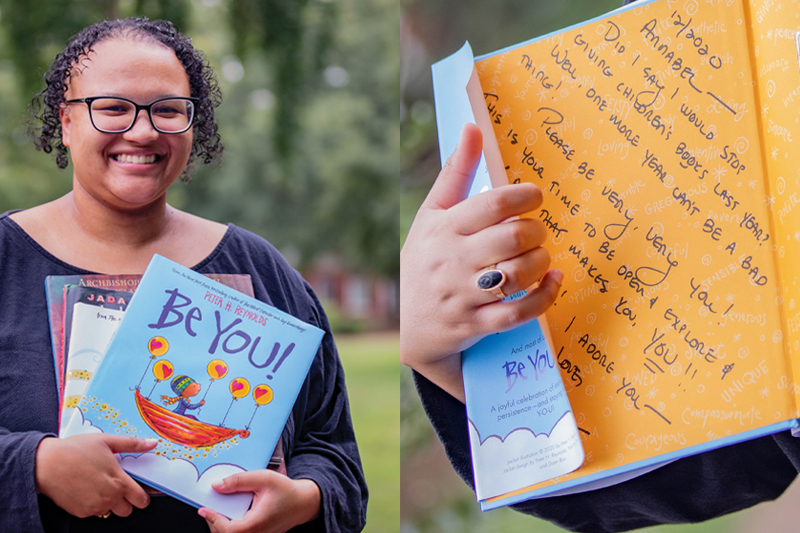

Annabel Hablutzel,’22

Student Adviser | Raleigh, North Carolina

“I self-identify as mixed or Black. I was born in Oklahoma City, but I was adopted, so I was immediately moved to New Hampshire. I’ve lived all up and down the East Coast my whole life, but I would say that North Carolina feels the most like home.

If I were to completely detail how my race has impacted my life, my response would be hundreds of pages long, so I won’t do that. I think that for people of color that just happens. It’s impossible to escape from it. In the context of my family, I always make sure to introduce my parents or sister as my family members, and right from the start I say I’m adopted. It helps avoid confusion or wrong assumptions. I think that for me and most adopted people who grew up in a family with a different race, it can be kind of confusing. You never really know what to identify as or what people think of you as.

I grew up in a family composed of all white people, so it was hard not to notice it. From the kids at school being confused, to some more dangerous encounters, people were always determined to point out that my family didn’t fit the cookie cutter shape.

One of the first times I remember realizing my identity was when the TSA pulled me aside because they thought my parents were trafficking me. I spent an hour or so being questioned, and they went through all of my things. It was terrifying, and from then on my parents carried my adoption paperwork when we traveled. People did things like this all of the time to my family. Strangers yelled at us and insisted that we couldn’t be family members. My family ended up developing a code to ensure we could signal when we were scared of people.

My parents have always been open and supportive of my identity. I remember being a part of adoption programs where kids who had been adopted could come together and hang out. However, I think that on the flip side, having to constantly defend my identity to the community has left sort of a bitter taste. It’s agitating to constantly have to clarify things. My identity is complex, and something I’ll be thinking about for many years to come.”

I volunteer at the SPCA.

Cats are one of my favorite animals.

I’ve lived in numerous places: New Hampshire, Connecticut, and in North Carolina: Raleigh, Chapel Hill, and Pittsboro.

I love tropical places. I really want to head back to Costa Rica.

Targeting (questioning, arresting, and detaining) people of color solely because of their “perceived race, ethnicity, national origin, or religion” often without appropriate evidence, is called racial profiling.

Machaela Murrell,’24

Summer Reading Committee Member | Durham, North Carolina

“First and foremost, I identify as a child of God. As a Christian this part of my identity is very important to me. My dad is partly the reason for this – he has been a pastor since I can remember so church has always been a part of my life. I also identify as a woman … specifically an African-American woman and I am proud of it. While there are many other things that make up who I am and how I identify, these are three big ones.

Durham, North Carolina, is home for me. I’ve lived in the same little yellow house since I was one year old so it’s all I know. The surrounding neighborhood has definitely had its share of ups and downs with violent crimes, drugs, and other things but what makes it peaceful is the community of neighbors. I would definitely say they are a second family to me.

Before the pandemic, my dad’s side of the family held a family reunion every year. Food is sort of how we bond so my aunts and uncles would prepare a huge meal and family would come from all over. Those moments are always special because it is a family tradition and a part of our culture.

Even though I sometimes struggle with feelings of self-doubt, I wouldn’t change who I am for anything. Being African-American is only a small part of who I am and while it is very important there are many other amazing things such as friendships and connections with other people that make me who I am.”

I was homeschooled my entire life.

I’ve played piano since I was four years old and I’ve played in church since I was 13.

I am a huge K-pop fan!

The United States has the largest Christian population in the world, with nearly 205 million Christians. According to a Pew Research Survey, 65% of adults in the United States identified themselves as Christians.

Rebecca Duncan

Summer Reading Committee Member | Northeastern Ohio

“I grew up in Northeastern Ohio, but that home as I knew it no longer exists. What was once a thriving industrial region is now sadly known as the Rust Belt. The population has shrunk significantly, and the area is ravaged by unemployment and problems like opioid abuse. In my traditional community, girls were encouraged to be teachers and nurses and eventually full-time homemakers. We were not given the encouragement to develop our talents that girls receive today.

I was always curious about different cultures and races. I spent a year in Brazil as an exchange student, and for one summer I worked at a camp for children from Harlem and Bedford Stuyvesant. Both were immersive experiences in being a minority. My fellow counselors and the children taught me to watch and listen, to question my assumptions, and to look for ways to connect. Any traces of the ‘white savior’ perspective were banished by the end of the summer.

I grew up in a time of mixed messages about race. Martin Luther King, Black Power, Michael Jackson, Diana Ross, Jimi Hendrix, and Motown all affected the culture of the times, but closer to home there always seemed to be an invisible barrier to incorporating new perceptions of race into our lives.

I would say that both family and community worked silently to maintain the status quo and the sense of a social hierarchy among the races. Thus, it was fine to be polite to the handful of Black kids at school, but I remember being called out for sitting with a Black student in the high school band. A performance by the group ‘Up with People’ was canceled by a youth club when the leaders found out there were Black singers. None of this sat right with me, but I was a mostly obedient, conformist kid and didn’t make a fuss.

Leaving home at the age of 18 and exploring the world through travel and education have broadened my perspective. As an adult, I have moved from conformist to rebel in many ways, and I have worked hard to break the cycle of prejudice in my own son’s experience.”

I have just finished writing a second novel.

I take part in an annual cookie baking competition and have won several championships.

I have worked, taught, or wandered in Brazil, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Bolivia, Morocco, and most of Western Europe.

White savior is problematic because it can seem to convey the power, superiority, and kindheartedness of the white person rather than the unjust system itself.

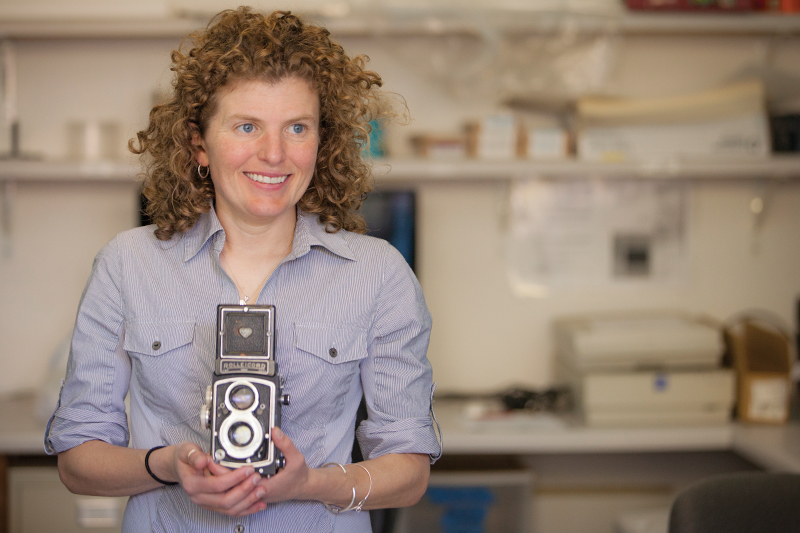

Shannon Johnstone

Summer Reading Committee Member | Milwaukee, Wisconsin

“I never thought of myself as having culture or race when I was younger. This way of thinking and being treated was an invisible padding that made walking through life in Milwaukee easier for me than it was for others. When I was by myself, I didn’t get the resistance or unfriendliness from people in authority that I experienced when I was with my friends who were not white. Milwaukee was (and still is) a very segregated city.

My oldest sister is Laotian. She came to live with us when I was 8, and she was 17. She is the oldest of a very large family and she had her own traditions, food, and a communication style with her family back in Laos that was very different from the way we lived.

I don’t think I had the words for it at the time, but I remember thinking about how complicated it was that she was part of my family but had her own family, and how differently we lived.

This was the first time I thought of myself as having a culture. It changed the way I saw the world, and led me to love photography. Photography is all about how you frame something, and how meaning is shaped by this perspective.

Race, culture, and identity are part of everything that we do. I think there is a tendency for humans to think they are unique in having awareness about these issues. But the desire for individuality while still belonging to something larger than oneself is found throughout many species all over Earth. This makes me realize how important thinking through all of this is – it is embedded in the foundation of living on this planet.”

I am an ultrarunner. My favorite ultra race is where you run as far as you can for 24 hours.

I was named to Team USA 24-hour National Team in 2014.

My favorite animal is the dog. I sometimes wish I had a tail to express myself.

As of 2010-14, Milwaukee was ranked as the most racially divided large city, followed by New York City and then Chicago.

Bianca Diaz

Summer Reading Committee Member | Miami, Florida

“I self-identify as a Cuban American woman. I was born in Miami and my family is from Cuba. I also identify as a daughter and granddaughter of immigrants; this is a particularly meaningful label for me because it allows me to honor my grandparents’ brave and difficult decision and incredible work ethic, and it connects me to a unique aspect of the American experience: coming to this country for a better, more stable future.

My Cuban culture has impacted my life in profound ways. I grew up speaking Spanish and English, and shifting between those two languages in my personal and professional lives is really rewarding. I love the moments I can connect with others who speak Spanish – it becomes this mental space where I feel comfortable and nostalgic; it’s a link to my whole family … the roots of my being. Spanglish is particularly enjoyable for me, too. I speak it with my parents, sister, cousins, my other bilingual friends and it becomes a special badge of connectedness and understanding between us.

The food in my culture is also something I relish! My paternal grandmother cooked traditional Cuban food and I have great memories of the dishes she made including arroz con pollo and frijoles negros.

I experience intersectionality in my identity as a Hispanic woman. This makes me feel fortunate because intersectionality breeds compassion: for others and myself. I first became aware of these aspects of my identity when I attended graduate school for creative writing in Virginia. I was the only Hispanic person in my cohort. Additionally, none of my professors were Hispanic or people of color. A visiting writer who was Indian and I spoke about intersectionality and how it could be a real advantage in our writing. That conversation helped me see that I should embrace the ways it could benefit my worldview and my art.

Growing up in Miami, I saw Cubans and other Hispanic people in positions of power and prestige: doctors, professors, attorneys, artists, community leaders, politicians, etc. Those examples stayed with me and allowed me to imagine myself in similar positions. I wouldn’t be an anomaly in my community, I’d be one of many.”

My favorite place I’ve visited is the Cliffs of Moher in Ireland.

I wrote a book of poems called No One Says Kin Anymore.

I love sushi.

I’m a first-degree purple belt in kickboxing.

Code-switching occurs when one alternates between different languages, dialects, or ways of speaking among different groups of people. “Spanglish” is the weaving together of English and Spanish within a phrase or sentence.

Key Terms

Source: Tell Me Who You Are: Sharing Our Stories of Race, Culture & Identity. The authors credit Racial Domination, Racial Progress by Matthew Desmond and Mustafa Emirbayer as the main source for the explanation of “Race.” Dilnavaz Mirza Sharma provided the definition of the term Parsee.

Colonialism

Occurs when a foreign power invades a territory and establishes enduring systems of exploitation and domination over that territory’s indigenous populations.

Intersectionality

The overlapping systems of advantages and disadvantages that affect people differently positioned in society. This means race cannot be examined in isolation from other social classifications like class, gender, religion, and sexuality.

Race

Race is a symbolic category based on attributes such as height, hair texture, eye color, and skin tone and ancestry. Race is not natural; it’s a well-founded fiction, a social construction rather than a biological truth.

Racial Equity

The condition that would be achieved if one’s racial identity no longer predicted, in a statistical sense, how one fares.

Whiteness

The dominant racial category that has become the norm. Other races are compared and contrasted relative to it, which is why people of color, rather than white people, are frequently identified by their race.